Michele Rodda

Botanical illustration has long been considered a critical aid for species identification and invaluable to taxonomic research (Blunt & Stearn, 1950; Oxley & Bebbington, 2017). However, the highly specialised and skilled artists responsible for these artworks often remain peripheral figures in institutional narratives. At the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG), a key artist is Juraimi bin Samsuri (1923–1971), yet his name remains largely unfamiliar—even within the botanical and art community, with extant information primarily limited to institutional Annual Reports, his obituary (Alphonso, 1971) and brief accounts in SBG’s magazine Gardenwise (Rodda, 2020; Soh, 2014).

This paper aims to start piecing together aspects of Juraimi’s life and contributions, highlighting his work within both the SBG’s scientific output and the broader mid-20th century Malay visual arts community.

The first mention of Juraimi’s interest in art is at age 13, about the prize he received for general proficiency in drawing at Victoria School, where he studied (Malaya Tribune, 1936). His association with SBG began in 1942, during the Japanese Occupation of Singapore when he was hired as a label printer. After the war, he was appointed as the official artist of the Gardens, until his premature death in 1971 (Alphonso, 1971).

The path to his artistic appointment lacks primary source documentation. The 1942 Annual Report provides a crucial clue: “The junior label printer, Juraimi, spent part of his time in making drawings of varieties of sweet potatoes and other vegetables under experimental cultivation, as the artist, Mr Chan York Chye, is working at the Museum.” This reference illuminates both Juraimi’s development and the broader context of artistic work at the Gardens. Subsequently, his role in the production of drawings of orchids (for Holttum), mushrooms (for Corner) and edible plants (for the Japanese botanists) is mentioned several times in the Annual Reports (Syonan Botanic Gardens monthly report, 1942; 1943). The quality of these works likely caught Gardens’ director Richard Eric Holttum’s attention, leading to his formal appointment as artist.

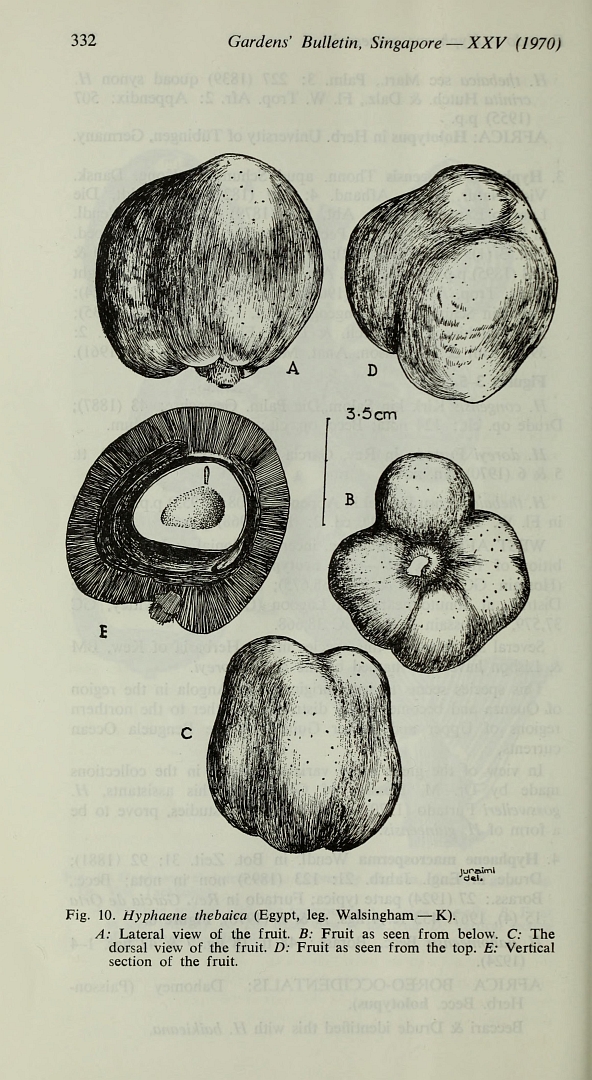

The artistic legacy of his nearly 30-year career as the Gardens’ sole—and first local—artist is carefully preserved in the nearly 400 watercolour paintings (Figure 1) and several hundred line drawings (Figure 2) preserved in the SBG’s archives, many of which were published in The Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore and significant publications such Gardening in the Lowlands of Malaya (Holttum, 1953).

Despite his work’s significance, little is known about Juraimi’s life, career trajectory, or working conditions. His name appears sporadically in SBG’s records and is absent from broader colonial administrative archives. While his residential address remains unknown, he likely lived in the SBG staff quarters.

While the botanists and administrators who built SBG’s global reputation are well-documented (Wong et al., 2014), Juraimi’s personal history remains elusive. One interpretation is that this reflects the broader patterns of archival erasure characterising histories of non-European staff in scientific institutions across the tropics (Arnold, 2000). It is also possible that the scarcity of records may also stem from practical issues—SBG’s archival materials have undergone multiple relocations, and a large part might be lost. Additionally, the extant archives are only now being systematically organised, databased and digitised, hopefully leading to the discovery of more records.

Media articles provide some insights to Juraimi’s life outside SBG. The Singapore Free Press and The Straits Times mention his involvement in the Singapore Malay Arts Class in 1949. Mentioned as “Juraimi bin Shamsu” he served as secretary and registration contact for an exhibition at the British Council Hall (The Singapore Free Press, 1949a; The Straits Times, 1949). He was also involved in the establishment of an “all Malaya Malay Artists Association”, later known as Persekutuan Pelukis Melayu Malaya (Society of Malay Artists, Malaya, or PPMM) (The Singapore Free Press, 1949b).

At the Gardens, Juraimi’s position was unique. It was not common practice to have a botanical artist employed full time—the last documented artist before him on the Gardens’ staff was Charles de Alwis from Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), employed until 1907. The Gardens never employed another full-time artist after Juraimi’s death in 1971, possibly both because of the rise of photography—a medium he much used in his final three years—and shifting institutional priorities. Juraimi was also the first SBG artist to be photographed at work (Figure 3), and he can be spotted among other staff in group photos in the SBG archives. His only known portrait appears in his obituary.

Juraimi’s art and contributions to botany have been increasingly highlighted in recent years. A selection of his works has been featured in the Botanical Art Gallery, SBG, since 2021, both as part of the permanent display and temporary exhibitions. He was also featured in the book Tropical Plants in Focus (Rodda, 2021), documenting the development of the botanical art collection at SBG. His early vegetable paintings, previously mentioned as potentially of crucial importance towards his employment as Gardens’ artist, are currently on display and complement the Botanical Art Worldwide 2025 Singapore exhibition (1 May – 2 Nov 2025) (Figure 4).

Certainly more extensive research is necessary to delve deeper into his working methods, relationships with other artists, and with botanists and other Gardens’ staff during the mid-20th century. His case like that or many others working in botanical institutions whose legacy survives through their productivity but whose lives remain obscure. How can institutions appropriately acknowledge such individuals? What can we infer from their material legacy? How do we place them within the institution’s scientific narratives?

Juraimi bin Samsuri was not merely a supporting figure in Singapore’s botanical legacy but one of its key contributors. His illustrations shaped our understanding of tropical plant diversity, and his legacy deserves thorough study and recognition as a vital component of Singapore’s scientific and cultural heritage.

.

References

Alphonso AG. 1971. Juraimi bin Samsuri Obituary. Gardens’ Bulletin, Singapore. 25(3): 385.

Arnold D. 2000. Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Blunt W, Stearn WT. 1950. The Art of Botanical Illustration. Collins, London.

Holttum RE. 1953. Gardening in the lowlands of Malaya. Singapore, Straits Times Press.

Malaya Tribune. 1936. Victoria School Prize Day. Malaya Tribune, 30 November 1936: 7.

Oxley V, Bebbington A. 2017. The Role and Value of Botanical Illustration Today. Eryngium 13: 3–9.

Rodda M. 2020. Drawings of vegetables during the Second World War. Gardenwise 55, back cover.

Rodda M. 2021. Tropical Plants in Focus, Botanical Illustration at the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Singapore, National Parks Board.

Soh C. 2014. Juraimi Bin Samsuri, the Gardens’ former resident artist Gardenwise 43, back cover.

Syonan Botanic Gardens monthly report. 1942. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/235296

Syonan Botanic Gardens monthly report. 1943. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/235617

The Singapore Free Press. 1949a. Malay Art Exhibition. 7 January 1949: 5.

The Singapore Free Press. 1949b. Malays Plan Art Society. 21 April 1949: 5.

The Straits Times. 1949. Malay Artists to Exhibit. 8 January 1949: 4.

Wong KM, Ganesan SK, Neo L, Furtado JIdR. 2024. The Botanists of the Singapore Botanic Gardens: The First 100 Years. Singapore, National Parks Board.