Malini Saigal

.

“The safety of the forest, to a great extent, depends on the exclusion from it of human beings.”

Dietrich Brandis, ‘Suggestions regarding Forest Administration in the Central Provinces’, 1876.

The archives at the Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh contain a wealth of forestry records from India. They made fascinating reading, especially the accounts from Kipling country in central India. By the 1850s unbridled logging by the East India Company gave way to organised forestry along German principles. Experimental gardens, new forest laws, and state ownership of community forests became the colonial norm.

The tall Sal (Shorea robusta) forests of central India were much prized by the British. But the other trees in the forest had little or no commercial value. The idea of a forest ecosystem, sustained and respected by forest tribes was alien to the Europeans. Among those misunderstood tribes were the Baiga, considered the earliest inhabitants of the land. Good-natured, devoted to the forest, and uncaring of possessions, they are still revered as magicians and healers by other communities, tribal or otherwise. They lived off forest produce and practised a form of shifting cultivation, much to the ire of the British foresters.

⬥⬥⬥

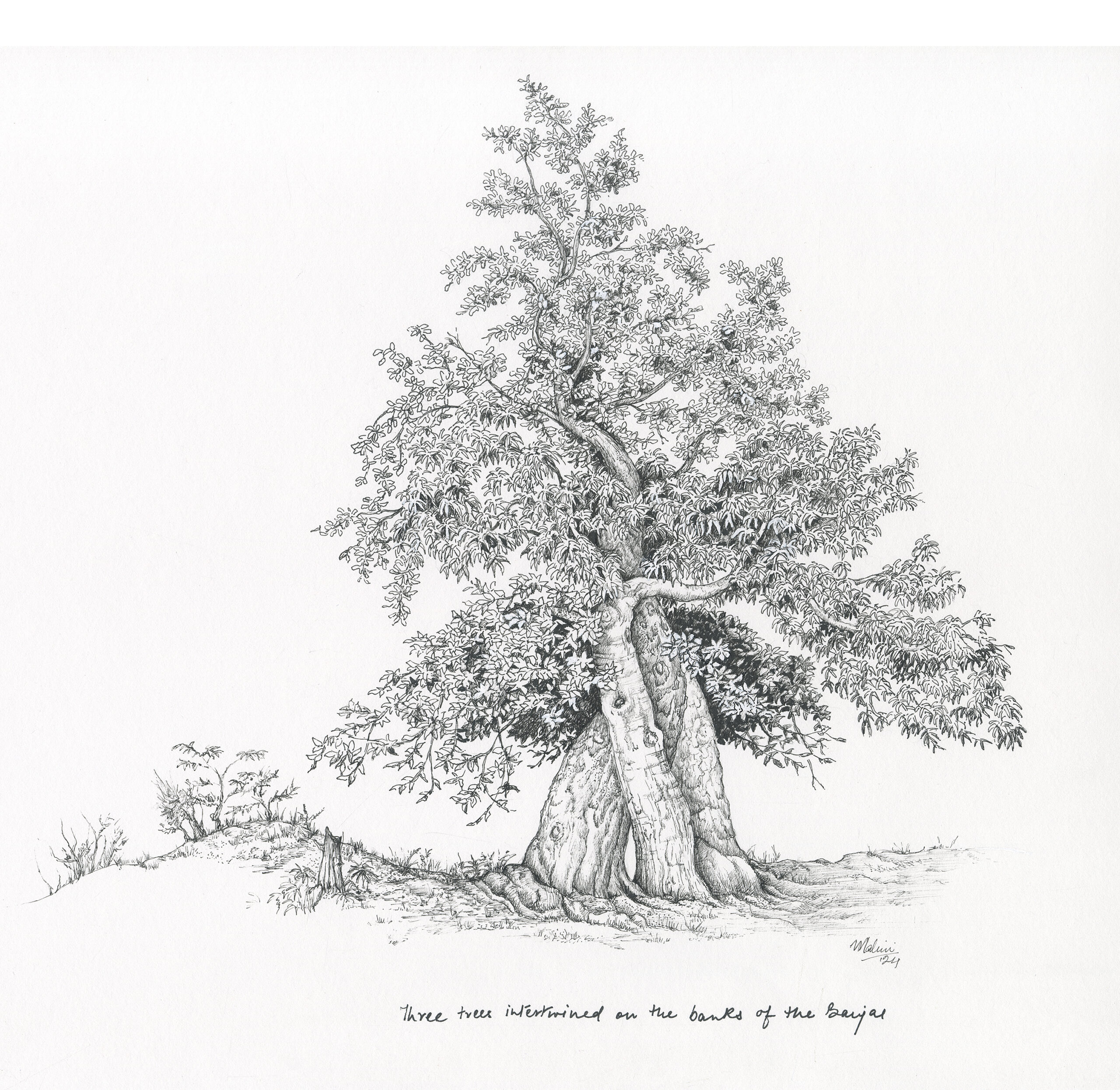

A variety of fig tree, very common near water sources.

Image: Malini Saigal.

.

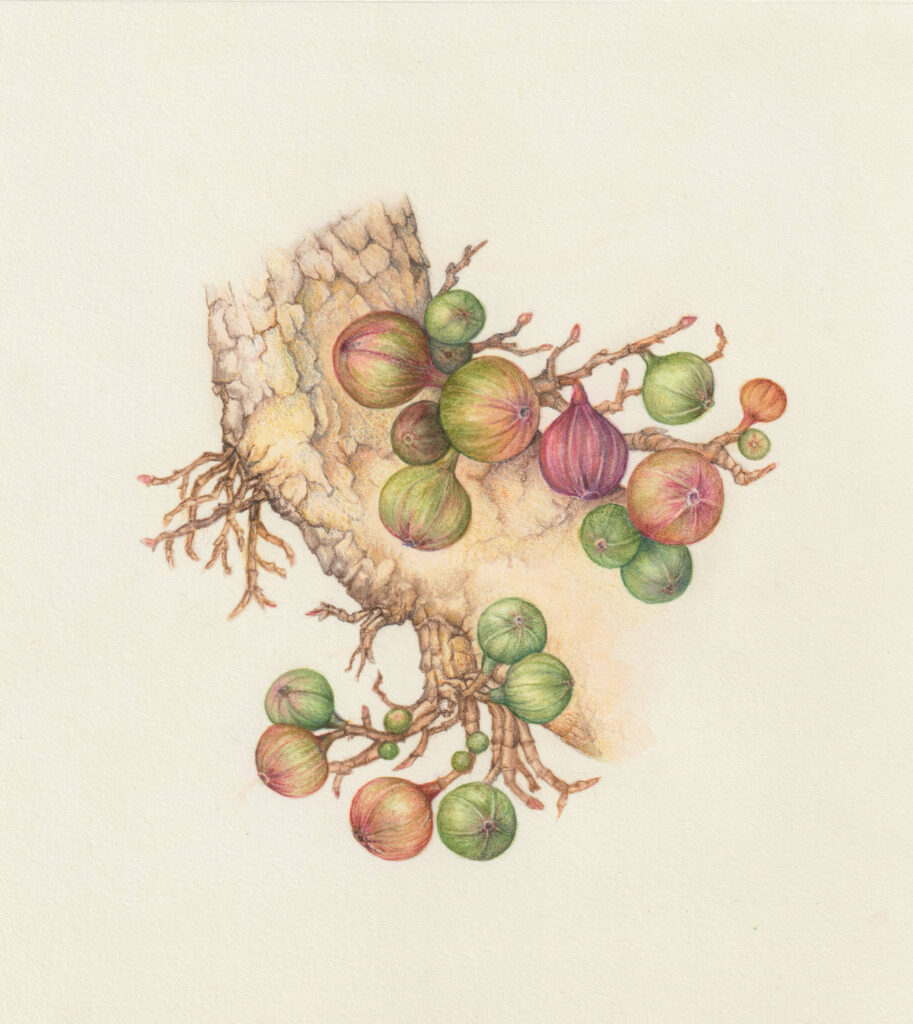

This summer, I visited a Baiga settlement deep in the forested Mandla district. The unfairness of history or the march of modernity has not dimmed their vast joy in nature. Trees are sacred, as many gods choose to live in them: Baradev (the senior god) lives in the Saaj (Terminalia elliptica) Thakurdev (the village god) lives in the Pipal (Ficus religosa) tree; Kheermata (the village goddess) prefers the Mahua (Madhuca longifolia); the Tamarind, Banyan and Baheda are similarly populated. Every festival begins at the base of a tree and young couples circle wooden posts to make their marriage vows. Demons are regularly exorcized and nailed to trees beyond the village boundary.

I stood outside a small, mud-plastered shrine, a searing noon sun burning through my clothes. Red and black flags atop two weathered wooden posts flapped loudly in the hot wind.

The shaman took his time explaining. “The gods are everywhere – in the wind, the cloud, the river, the earth, the tiger, the birds, and even the insects. Our Baradev lives in the Saaj tree. And Kheermata lives in the Mahua tree. These khambas (posts) are from those trees.”

“How do you worship them?”

“Oh, it’s best to give each what they want. Some like chicken, some like goat, others like rice, alcohol, honey, or tobacco. Each to their own! Then everyone is happy.”

Truly a practical philosophy for the ages. Pity it was so rarely followed.

⬥⬥⬥

Image: Malini Saigal.

.

Emperor Ashoka (3rd century BCE), a warrior turned pacifist, had his pronouncements on law and life carved onto stones and tall pillars throughout his vast empire. Scholars have linked these pillar edicts with the ancient cult of the axis mundi, the central staff separating the earth and the sky, and with Near Eastern, Egyptian, and Nordic mythology. Perhaps, but it is also possible that Ashoka knew that his diverse subjects revered trees and wooden poles. What better way to impart his royal views than to co-opt an existing symbol of divine authority?

I peered up at an ancient sandstone pillar in a small field beside a thatched settlement. A plaque stated that it was erected in the second century BCE by Heliodorus, a Greek visitor to the court of a local king, to honour the Hindu god Vasudeva or Vishnu.

But all that doesn’t matter to the villagers, who for centuries have accepted the pillar as the home of a benign guardian spirit called the ‘Khamba baba’.

“He has great powers,” explained a beaming village grandmother. “We offer grain, fruit, flowers, even liquor, in return for his protection against thieves, illness, drought, anything that troubles us.”

She pointed at an adjacent tamarind tree with iron nails embedded in its trunk. “He pulls out the demons that possess folks and nails them to the tree. They are trapped there forever, their power destroyed.”

‘What if they escape?’ An arboreal jail didn’t sound too secure.

“Khamba baba will catch them. Besides, the tree won’t let them.”

⬥⬥⬥

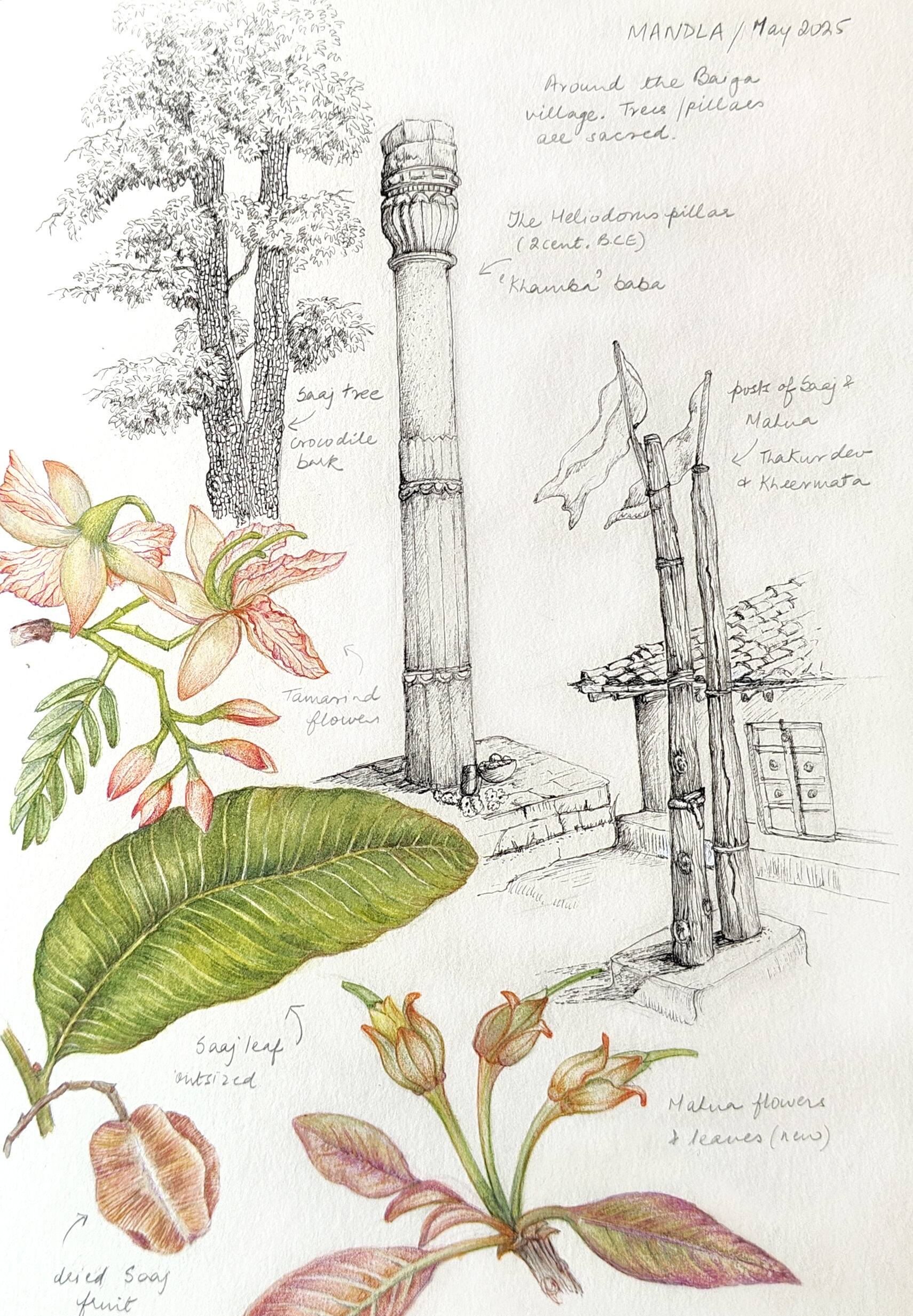

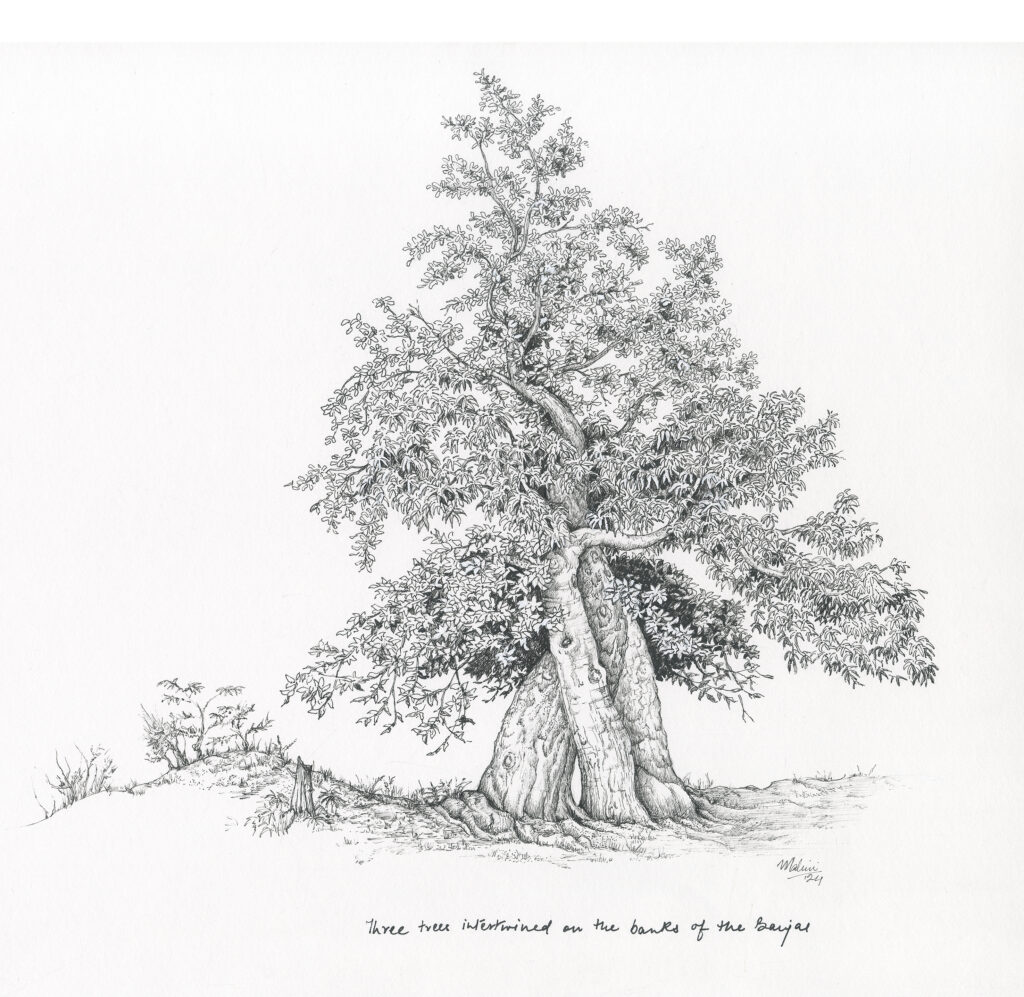

This was a lovely sight of 3 entwined trees on the banks of the Banjar river in the forest– Gooler (Ficus racemosa) , Baheda ( Terminalia bellirica) and Jumkitni (Syzygium salicifolium).

Image: Malini Saigal.

.

I walk down the forest path, my feet crunching over the piles of dry leaves. I have a list of 22 endemic trees that I need to find, sketch and paint. My guide, Dharmu, is patient and painstaking. He belongs to the Gond tribe and has grown up in this jungle.

Dharmu reached up for a scented white flower on a gnarled branch. “This is Poniyabillo. Its flowers turn from white to yellow.”

“But it looks the same as Deekamalli?” I peer at my phone camera, looking for the best angle.

“It does, but with Deekamalli, if you crush the fruit it smells like asafoetida. This is a different tree.”

And so on. At the end of three hours, I could identify only nine with certainty. How exactly did the Scottish botanists achieve so much documentation without cameras, electricity or let’s be frank, the internet?

Surgeons turned botanists turned administrators created a wealth of resources for Indian flora, only to add to the larger wealth of England. It’s an interesting dichotomy worth exploring. Did they all agree with the forestry policies laid down by Dietrich Brandis, the Inspector General of Forests in India from 1864 to 1883, aptly summed up by his protégé, B. Ribbentrop:

“A great part of India’s population was (and is) weaned only with the greatest difficulty from their pastoral, semi-nomadic habits, and wasteful methods of cultivation, as practiced by savage and early settlers.” (Forestry in British India, 1900)

Or were there some who saw the age-old wisdom of tribal lifestyles and did not consider them uncivilised or wasteful? Perhaps lauded the tribals for their knowledge of local flora and fauna and traditional conservation practices. Even Brandis noted that sacred groves were abundant and useful.

Thoughts swirl in my head. Of my list of 22 trees, how many were studied and painted in the 19th century by the Scottish botanist-explorers? Did they link them to the lives of the people in the area? A useful exercise would be to look at both official and personal records of the men and women who spent their lives in the heart of colonial India.

After all, a forest is not just trees. It is a landscape like any other—farm, city, mountain or desert–that sustains those that live there. It is also not just a biotic reservoir, but an endless fount of legend and logical, sustainable living. Humans are very much part of any ecosystem.

Dharmu summed up his current dilemma. ‘We get nearly everything from the land and the forest. Food, fuel, medicines, thatch. All our festivals are around the seasons. That is an unchanging natural law.

My father taught me everything, but my children are just not interested. All they want is the mobile phone and shiny things. Our centuries-old knowledge will die with my generation…You see, people change, then what can Mother Earth do?”

I left the jungle with more questions than answers. What have humans wrought in the name of progress? What is progress, really? Is the tribal faith in nature a naïve belief or a profound truth? Surely there must be a way to harness this belief to redress the damage of the colonial past and the unplanned present.

.